| |

| |

Caption: Book - Research on Campus (1949)

This is a reduced-resolution page image for fast online browsing.

EXTRACTED TEXT FROM PAGE:

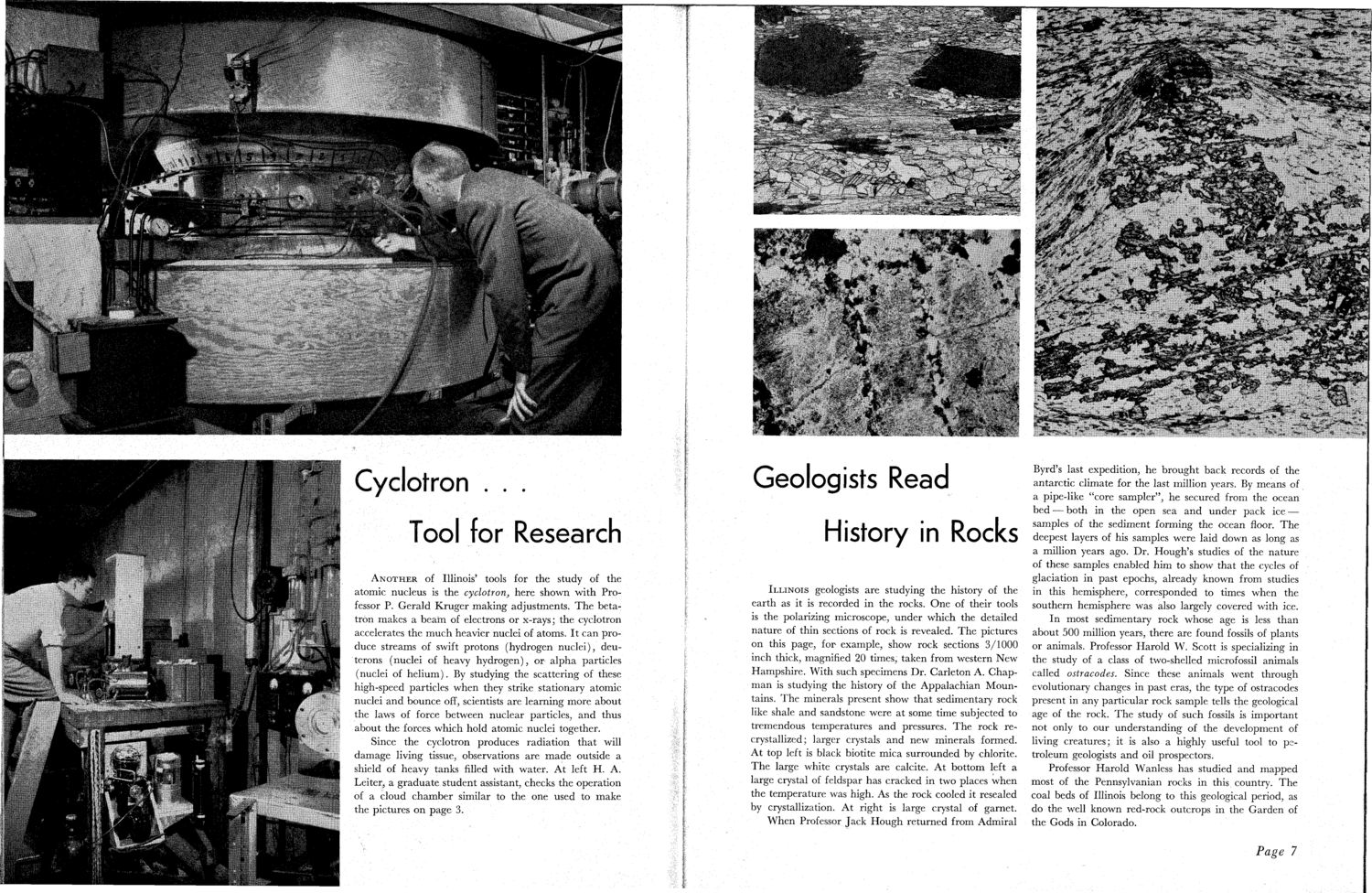

Cyclotron . . . Tool for Research A N O T H E R of Illinois' tools for the study of the atomic nucleus is the cyclotron^ here shown with Professor P. Gerald Kruger making adjustments. T h e betatron makes a beam of electrons or x-rays; the cyclotron accelerates the much heavier nuclei of atoms. It can produce streams of swift protons (hydrogen nuclei), deuterons (nuclei of heavy hydrogen), or alpha particles (nuclei of helium). By studying the scattering of these high-speed particles when they strike stationary atomic nuclei and bounce off, scientists are learning more about the laws of force between nuclear particles, and thus about the forces which hold atomic nuclei together. Since the cyclotron produces radiation that will damage living tissue, observations are made outside a shield of heavy tanks filled with water. At left H. A. Leiter, a graduate student assistant, checks the operation of a cloud chamber similar to the one used to make the pictures on page 3. Geologists Read History in Rocks ILLINOIS geologists are studying the history of the earth as it is recorded in the rocks. One of their tools is the polarizing microscope, under which the detailed nature of thin sections of rock is revealed. The pictures on this page, for example, show rock sections 3/1000 inch thick, magnified 20 times, taken from western New Hampshire. With such specimens Dr. Carleton A. Chapman is studying the history of the Appalachian Mountains. T h e minerals present show that sedimentary rock like shale and sandstone were at some time subjected to tremendous temperatures and pressures. T h e rock recrystallized; larger crystals and new minerals formed. At top left is black biotite mica surrounded by chlorite. T h e large white crystals are calcite. At bottom left a large crystal of feldspar has cracked in two places when the temperature was high. As the rock cooled it resealed by crystallization. At right is large crystal of garnet. When Professor Jack Hough returned from Admiral Byrd's last expedition, he brought back records of the antarctic climate for the last million years. By means of a pipe-like "core sampler", he secured from the ocean bed — both in the open sea and under pack ice — samples of the sediment forming the ocean floor. T h e deepest layers of his samples were laid down as long as a million years ago. Dr. Hough's studies of the nature of these samples enabled him to show that the cycles of glaciation in past epochs, already known from studies in this hemisphere, corresponded to times when the southern hemisphere was also largely covered with ice. In most sedimentary rock whose age is less than about 500 million years, there are found fossils of plants or animals. Professor Harold W. Scott is specializing in the study of a class of two-shelled microfossil animals called ostracodes. Since these animals went through evolutionary changes in past eras, the type of ostracodes present in any particular rock sample tells the geological age of the rock. T h e study of such fossils is important not only to our understanding of the development of living creatures; it is also a highly useful tool to petroleum geologists and oil prospectors. Professor Harold Wanless has studied and mapped most of the Pennsylvanian rocks in this country. The coal beds of Illinois belong to this geological period, as do the well known red-rock outcrops in the Garden of the Gods in Colorado. Page 7

| |