| |

| |

Caption: Board of Trustees Minutes - 1884

This is a reduced-resolution page image for fast online browsing.

EXTRACTED TEXT FROM PAGE:

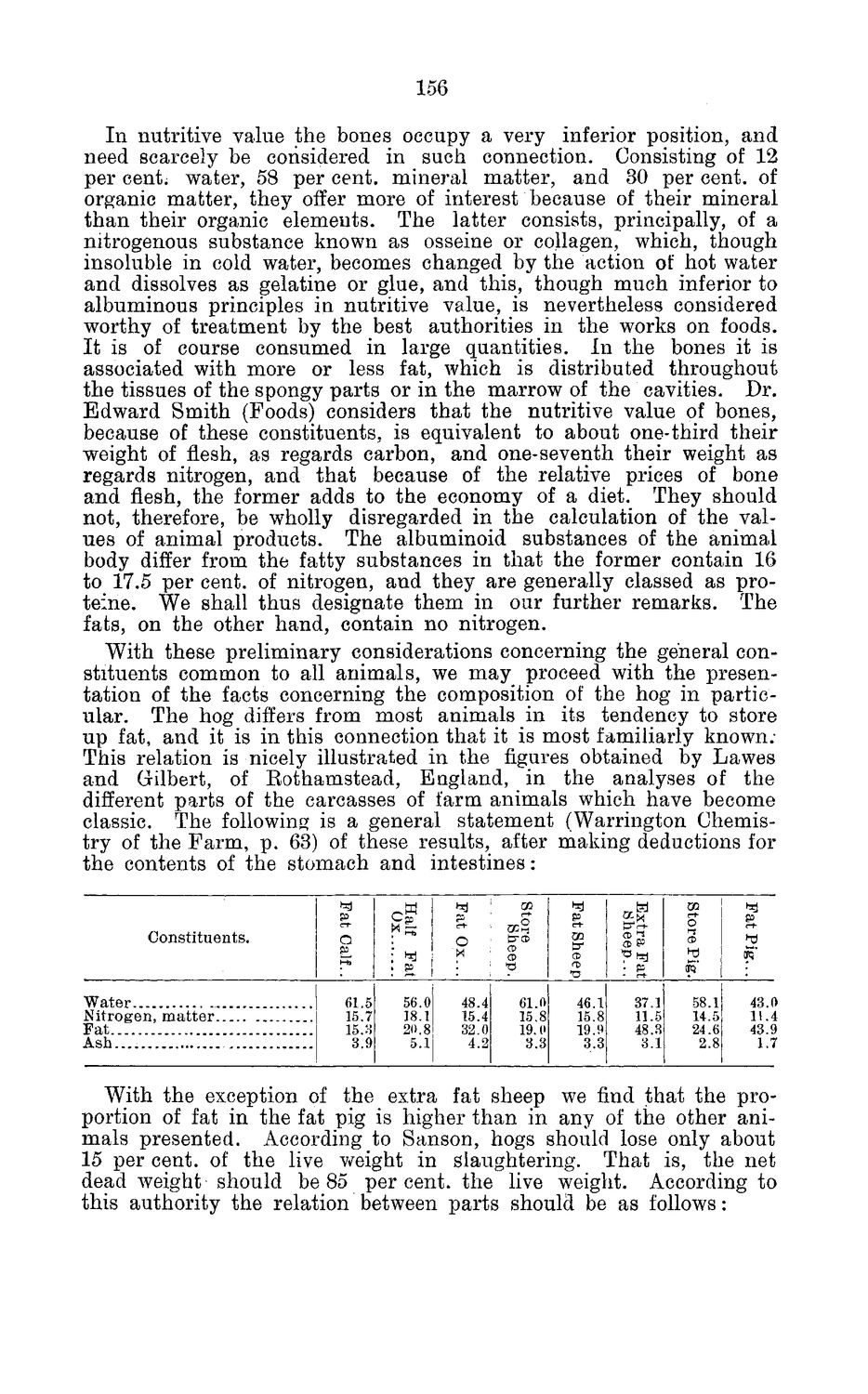

156 In nutritive value the bones occupy a very inferior position, and need scarcely be considered in such connection. Consisting of 12 per cent, water, 58 per cent, mineral matter, and 30 per cent, of organic matter, they offer more of interest because of their mineral than their organic elements. The latter consists, principally, of a nitrogenous substance known as osseine or collagen, which, though insoluble in cold water, becomes changed by the action of hot water and dissolves as gelatine or glue, and this, though much inferior to albuminous principles in nutritive value, is nevertheless considered worthy of treatment by the best authorities in the works on foods. It is of course consumed in large quantities. In the bones it is associated with more or less fat, which is distributed throughout the tissues of the spongy parts or in the marrow of the cavities. Dr. Edward Smith (Foods) considers that the nutritive value of bones, because of these constituents, is equivalent to about one-third their weight of flesh, as regards carbon, and one-seventh their weight as regards nitrogen, and that because of the relative prices of bone and flesh, the former adds to the economy of a diet. They should not, therefore, be wholly disregarded in the calculation of the values of animal products. The albuminoid substances of the animal body differ from the fatty substances in that the former contain 16 to 17.5 per cent, of nitrogen, and they are generally classed as proteine. We shall thus designate them in our further remarks. The fats, on the other hand, contain no nitrogen. With these preliminary considerations concerning the general constituents common to all animals, we may proceed with the presentation of the facts concerning the composition of the hog in particular. The hog differs from most animals in its tendency to store up fat, and it is in this connection that it is most familiarly known: This relation is nicely illustrated in the figures obtained by Lawes and Gilbert, of Rothamstead, Eugland, in the analyses of the different parts of the carcasses of farm animals which have become classic. The following is a general statement (Warrington Chemistry of the Farm, p. 63) of these results, after making deductions for the contents of the stomach and intestines: _._ . . Fat Calf.. Fat Sheep Extra Fat Sheep... Store Sheep. Half Ox Fat Ox... Store Pig. Fat Pig... Constituents. Fat 56.0 18.1 20.8 5.1 Water Nitrogen, m a t t e r Fat Ash.... 61.5 15.7 15.3 3.9 48.4 15.4 32.0 4.2 61.0 15.8 19.0 3.3 46.1 15.8 19.9 3.3 37.1 11.5 48.3 3.1 58.1 14.5 24.6 2.8 43.0 11.4 43.9 1.7 With the exception of the extra fat sheep we find that the proportion of fat in the fat pig is higher than in any of the other animals presented. According to Sanson, hogs should lose only about 15 per cent, of the live weight in slaughtering. That is, the net dead weight should be 85 per cent, the live weight. According to this authority the relation between parts should be as follows:

| |